Plans to Build Public School Next to Toxic Superfund Site Raise Community Alarm

A proposed school in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, has raised concerns about potential health risks due to its proximity to a Superfund Site. Community members are demanding better dialogue with officials.

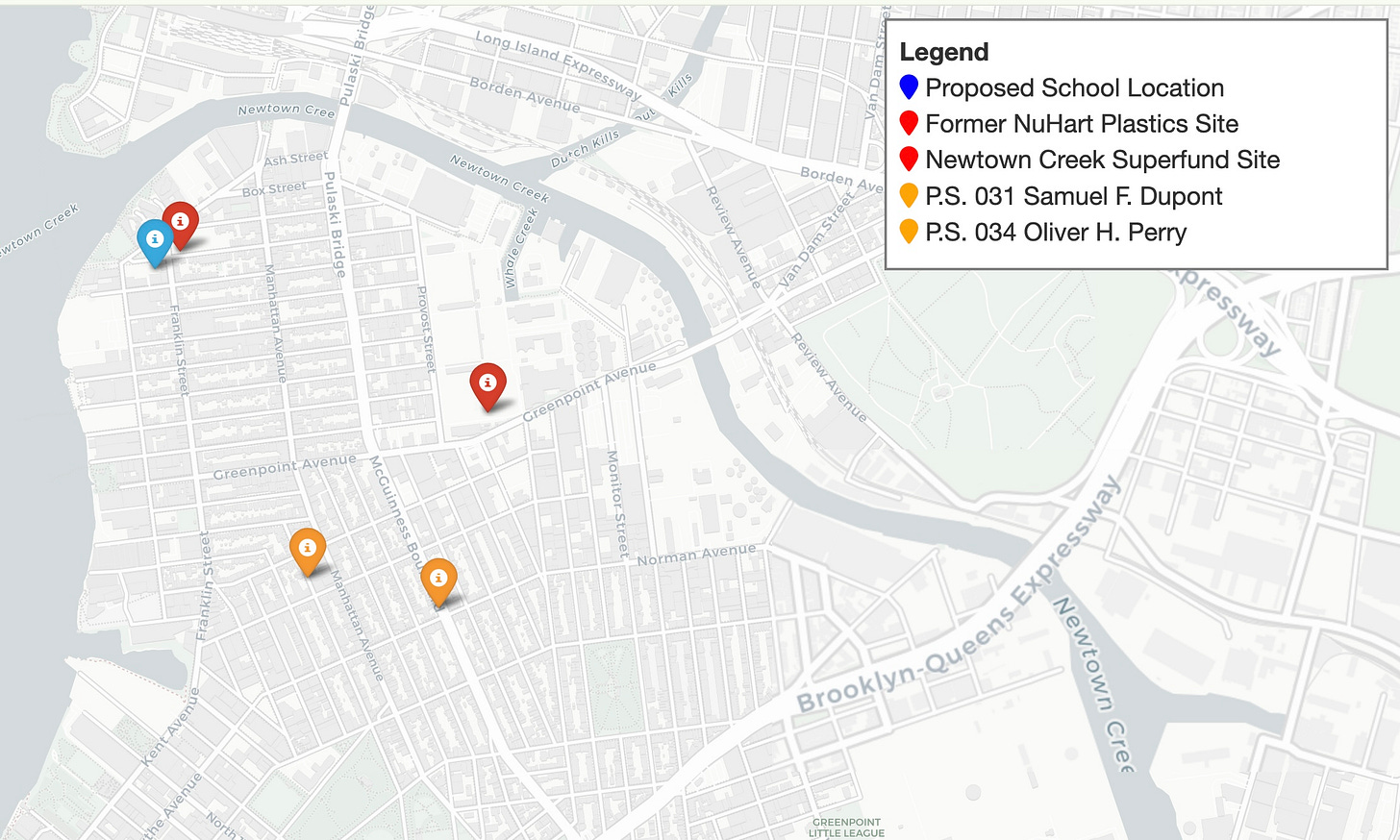

The New York City School Construction Authority (SCA) is moving forward with plans to construct a new elementary school at 257 Franklin Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The proposed school would be located directly across from the NuHart Plastics Superfund site, a former industrial plant infamous for its toxic past.

The NuHart Plastics facility operated from 1950 to 2004, producing plastic and vinyl products during its time. The factory was shut down by the state after toxic chemicals were found leaking into the nearby environment. It was officially designated a Superfund site in 2010, continuing a hazardous legacy in Greenpoint.

The soil and groundwater of the former facility remain contaminated with phthalates, chemicals linked to developmental health risks, and trichloroethylene (TCE), a known carcinogen. Although cleanup efforts are ongoing, significant concerns about residual contamination persist.

Local residents and environmental advocates are expressing alarm over the proposed school's proximity to the toxic site. They argue that the site's history of contamination poses an unacceptable risk to students and staff.

"No child should have to go to school next to a toxic waste site," stated a petition by North Brooklyn Neighbors, a nonprofit dedicated to environmental justice. “But a generation of Greenpoint children will unless an alternate location for a future school is found.”

The petition has garnered over 6,700 signatures.

The School Construction Authority insists that extensive environmental assessments have been conducted, and that no contaminants have been detected on the proposed school property.

The SCA proposed further safety measures, including installing a hydraulic barrier to prevent underground toxin migration and constructing the school without a basement to mitigate the risk of vapor intrusion.

Even with these assurances, skepticism among some residents remains.

“We want schools,” said Susan Caldwell, a long-time Greenpoint resident. “But not at the cost of our kids’ health. Greenpoint deserves better.”

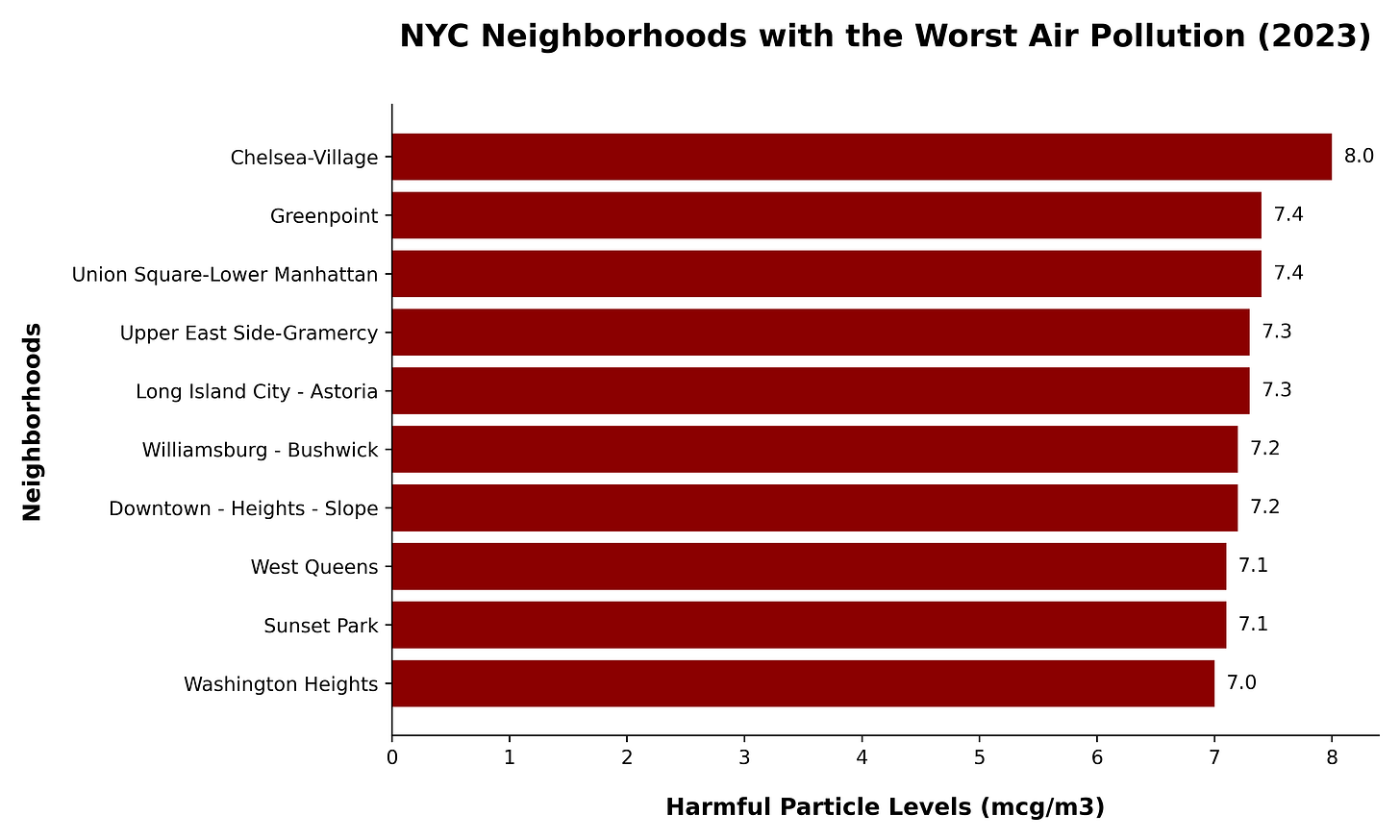

Greenpoint has long struggled with environmental challenges, the most striking example being the 1978 Greenpoint oil spill, one of the largest in U.S. history. An estimated 17 to 30 million gallons of petroleum products spilled into the surrounding soil and waterways.

Nearby Newtown Creek, another Superfund site, further highlights the area’s toxic burden. In 2022, Greenpoint became the only New York City neighborhood with two EPA-designated Superfund sites.

Efforts to address Greenpoint’s toxic legacy include the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund, established as part of a settlement with ExxonMobil over the oil spill. The fund has supported local projects aimed at improving the neighborhood’s environment.

Yet the scars of industrial pollution remain deeply ingrained, influencing local development decisions and fueling ongoing debate.

“We urgently need a new elementary school in Northern Greenpoint,” said Council Member Lincoln Restler, who represents the region. “But we are committed to soliciting community feedback to determine if this is the right location.”

The SCA has scheduled a virtual town hall on January 22 to address community concerns and provide further details on the proposed school’s safety measures. Residents are encouraged to participate and voice their opinions.

The clash between the urgent need for more schools and the responsibility to protect public health underscores the complexities of urban development in communities burdened with industrial legacies.